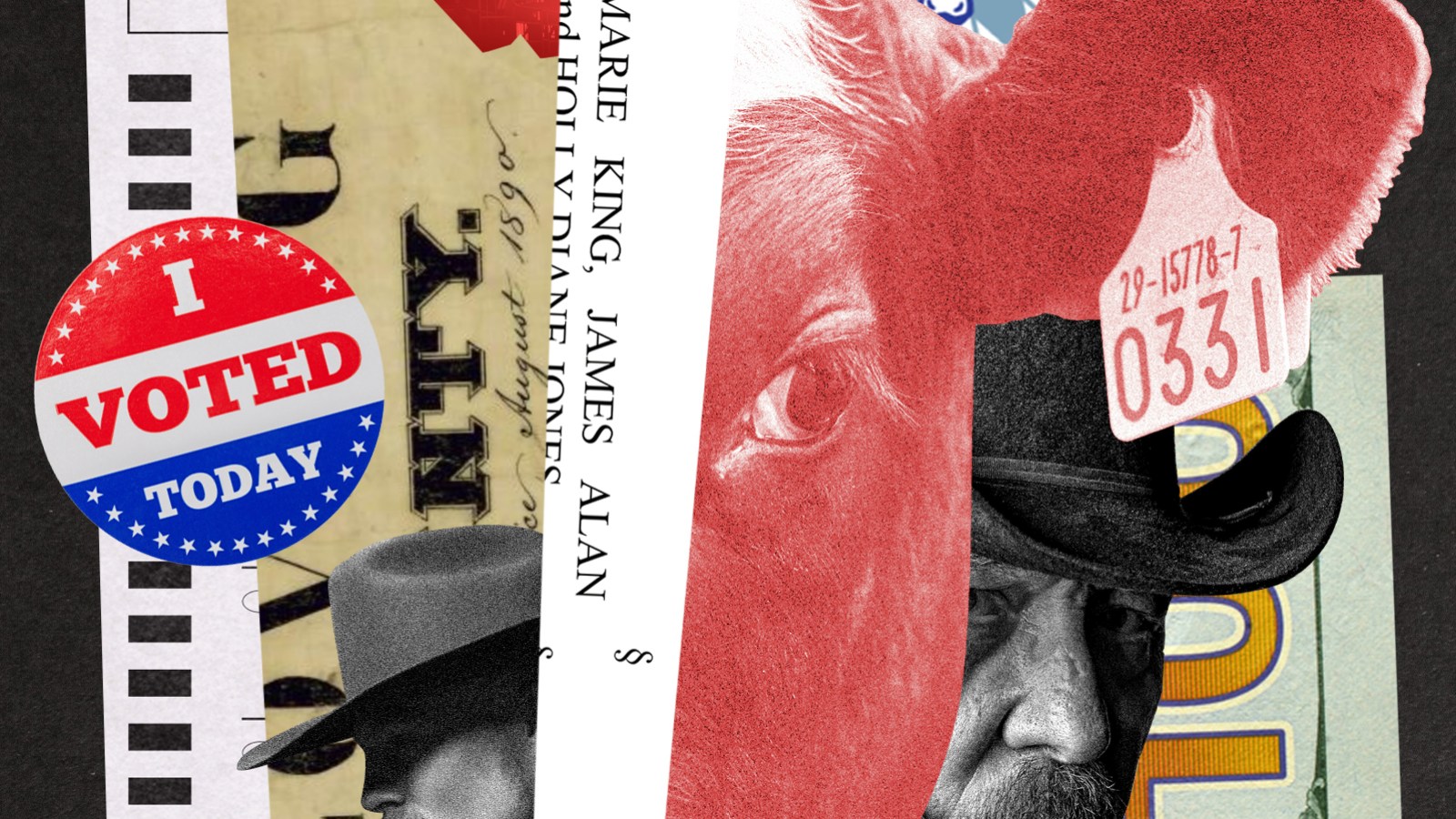

‘It’s Money and Greed’: Oil, Politics, and Dead Cows in a Small Texas County

This story is published in partnership with AT WILL MEDIA.

March 2, 2021. A cool, clear morning. An open highway in West Texas.

A lawman named Marty Baker cruised down state Highway 302, strewn with rubber truck-tire shreds that looked like black eels. The landscape around him was parched and coated in a layer of pale-green mesquite, the vast horizon punctuated by oil pumps, processing tanks, and natural-gas flares. Baker was heading 96 miles from Midland, Texas, to Loving County in the heart of the Permian Basin, the highest-producing oil field in the country. His destination was a spot just west of Mentone, the county seat, a dusty outpost of around 13 residents with a courthouse, scattered trailer homes, a gas station, and a few taco stands and eateries catering to the 15,000 oil field workers and drivers who pass through the county each day. A special ranger for the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association responsible for livestock crimes, Baker was responding to a call about some cattle shot dead on the side of the road. Baker was in his late-fifties, a no-nonsense investigator with more than 35 years of experience, tall and thin with a bald head under a cowboy hat, prominent smile lines, and a steel-grip handshake. He grew up in Coleman, Texas, square in the middle of the state. The nickname for his job was “cow cop,” but it was serious work: In Texas, killing or stealing a cow can lead to up to 10 years in prison.

Loving County, which stretches more than 660 square miles and borders New Mexico, is the least populated county in the United States, with roughly 50 to 60 full-time residents, according to estimates. Oil was discovered there in the 1920s, and the county went through booms and busts for decades, enriching wildcatters and devastating the landscape, until a lasting bust left Loving County a virtual wasteland with no running water, paved roads, schools, hospitals, or grocery stores. Then, in the early 2010s, fracking and horizontal drilling technology unlocked the deposits hiding in the shale bed and unleashed vast wealth that went beyond the county residents’ wildest dreams.

That day, Baker pulled up to the scene of the crime, where he found a group of ranch hands loading the carcasses, five in total, onto the back of a flatbed trailer. He chatted with sheriff’s deputies and snapped photos of the dead animals as the men worked. It was an odd scene: There were no footprints, shell casings, or tire tracks, and the deputies said they had no idea who might be behind the shootings.

Editor’s picks

A shorter man in his early seventies with dark, squinting eyes and a raspy voice came over to Baker and extended a hand. “Skeet Jones,” the man said.

Jones was the county judge, and the ranch hands at the scene worked for his nearby property, the P&M Jones Family Ranch, where he said they were planning to haul the remains. Jones himself had made the call about the cattle. Baker thought it was slightly unusual that the county judge was personally at the scene, but Jones acted as if nothing was out of the ordinary. Not long before, a cow had been struck and killed on the side of the road nearby in Reeves County. Jones figured someone from law enforcement probably shot the cattle to prevent another accident.

Marty Baker was the special ranger responsible for livestock crimes in Loving County.

Photograph by Michael Magers

Jones explained that he and his ranch hands had been trying to capture the strays for days, setting out pens with water to lure them in and monitoring them with night-vision goggles. He told Baker they were planning on selling the animals at auction and donating the money to a ranch for at-risk boys. This, too, struck Baker as strange. Texas has stringent estray laws, a process that involves public notices to find the owner and coordination with the Sheriff’s Office. Baker didn’t want to argue with the judge, but he did discuss the state’s regulations with him. Jones said he was familiar with them.

Related Content

Baker left the county later that day with a sense that something was off. He did some investigating over the phone and spoke with Jones a few more times. Jones was the patriarch of the most prominent family in Loving County and the most powerful figure there, serving as a county commissioner before becoming judge in 2007. Many of his relatives worked in county jobs and his late father, Elgin “Punk” Jones, was county sheriff for nearly 30 years.

Baker returned to Loving County several times during his investigation into the cattle killings. He interviewed members of the community who quietly told him to look into the activities of the Jones family, namely Skeet himself. The judge, he learned, was a charismatic and cunning figure. “He is a charming guy,” Baker says of Jones in a deep Texas timbre when we meet him in his windowless, dimly lit office in Coleman, Texas, 271 miles east of Mentone, where he was serving as chief of police. Baker sits behind a large desk, periodically consulting his report from the case — the strangest of his career, he says — which is pulled up on his computer screen. It’s been more than three years since the case began, and he’s still mystified by it. “He is a silver-tongue devil. He is the kind of guy that will be in that courtroom and get up there on the stand and talk that jury plumb out of a guilty verdict. He is that smooth.”

Baker began to suspect that the investigation was bigger than just a few dead cows on the side of the road: He might be dealing with an organized cattle-rustling ring led by a powerful county judge. He came up with a plan to find out for sure.

What Baker didn’t know was that his investigation would add fuel to a family feud in the county with roots generations deep — with accusations of vote rigging, corruption, harassment, threats of violence, even Divine retribution — that was about to tear the county’s most dominant political clan in two. On one side of the conflict was Skeet and many of his immediate family members and longtime allies; on the other was Skeet’s own nephew, Constable Brandon Jones, who came to represent those who had run afoul of his own family. As county attorney Steve Simonsen describes the conflict when we meet in his office in the Mentone courthouse: “This is not quite the Hatfields and McCoys. It’s like the Hatfields and Hatfields, right? I mean, it’s brother against brother, uncle against nephew.”

The story of the bitter conflict ripping Loving County apart is inseparable from its history, one of hardship, survival, and ties to an unforgiving place that are born deep inside a person’s bones like marrow. It’s the story of when the outside world came to an extremely isolated place where one family held an iron-tight grip on power for decades — a story of personal animosity, grievance, impunity, resistance to change, and ego. And when billions of dollars of oil money began flowing through the county, it added kerosene to an already burning fire.

ON THE DRY AND BRIGHT morning of Aug. 14, 2024, I pull up to Mentone’s two-story yellow brick courthouse. I’m here to meet Skeet Jones, or at least try to — he hasn’t answered or returned my calls to his office. I’m a little nervous as I prepare my tape recorder in the driver’s seat of a rental car. I’ve been in the area for the past few days, staying in Pecos, a small city in neighboring Reeves County, a 20-minute drive from Mentone, and several people have told me I’ve probably been surveilled during my stay.

Loving County can be a shocking place to visit for an outsider, a vast terrain ravaged by elements and industry, a landscape and atmosphere somewhere between Mad Max and No Country for Old Men. Tensions are so high that visiting the place and speaking to its residents can feel like stepping into an episode of a television drama moments before the murder at the center of the plot takes place. There aren’t many obvious or ostentatious signs of wealth, other than a few pristine trucks and SUVs in the courthouse parking lot, and a new community center in Mentone that cost millions and is barely used. But the setting disguises the extraordinary riches hidden behind the barbed-wire fences and buried under the sun-baked soil — the taxable oil and gas revenue in Loving County is a staggering $11.7 billion. Today, satellite images taken at night show Loving County lit up brighter than major urban centers like Dallas and Houston because of the scale of oil and gas activity.

Pretty much everyone in the county has benefited financially from the fracking boom. Landowners sold mineral, land, and water rights to oil and gas companies. The oil fields created jobs, and the workers supported the local businesses. Oil money bought the county new paved roads, a large community center, and a new water system. Government work has become increasingly lucrative: Many county positions pay an annual salary of $126,000, with full benefit packages. Even the county custodian is rumored to make six figures.

In the courthouse, I walk past an arrowhead collection in a glass case and a framed black-and-white photo of Skeet’s father, Punk, who, with his chiseled features and cowboy hat, looks like a character from a John Wayne Western. I reach the reception area, where a small group of people work and chat. A woman with flowing white hair sits behind the desk. This is Mozelle Carr, Skeet’s sister and the county clerk. As I introduce myself, Carr and the rest of the workers look at me in a way that suggests they have no clue who I am or why I’m here. Perhaps I haven’t been followed after all.

I tell Carr I’m working on a story about Loving County and its history, and almost immediately a man in jeans, a cowboy hat, and protective glasses normally used at shooting ranges runs down the hall to consult with the judge. I recognize him as Leroy Medlin, the county custodian and a ranch hand at the Jones Ranch. Medlin, I’ve recently learned, was once a detective with the San Antonio Police Department who, according to news reports, was fired for initiating unnecessary high-speed chases. He then briefly worked as a deputy in the Loving County Sheriff’s Office before being taken on by Skeet as the courthouse custodian. (Medlin declined to be interviewed for the article.)

Moments later, Medlin returns to the reception area. “He wants to refer you to the attorneys because they’re getting ready to make a statement about all the crap that’s been going on,” he says. Medlin escorts me down the hall to the judge’s office, where Skeet is in a meeting with some local men.

Loving County stretches more than 660 square miles and borders New Mexico.

Photograph by Michael Magers

When Skeet invites me in, I ask if he’s willing to do an interview. “I can talk to you about the history, but not about the ongoing political mess they’re having,” he explains. “Yeah, we got a lot of mess going on. A lot of good stuff.”

Skeet is a diminutive figure with short, gray hair, and a round face with prominent cheeks. He speaks in a soft voice, interrupted frequently by bursts of almost childlike laughter. He sits behind a large, L-shaped red-oak desk strewn with papers. He’s wearing blue jeans, boots made of ostrich leather, and a gray button-down shirt with red and yellow pens in the chest pocket, backlit by the morning sun shining through the window behind him.

With little prompting, Skeet launches into a series of yarns about the history of the county. And it’s a wild history. Loving County was founded on blood and corruption. Its namesake, cattleman Oliver Loving, was shot by a band of raiders during a cattle drive in 1866, and died of shock a few days later after a doctor didn’t amputate his gangrenous arm. The county’s first elected officials absconded with the county treasury a few years after it was founded in 1887. As a result, the county was dissolved in 1897 and reorganized again in 1931.

Skeet was born in 1951 in next-door Winkler County, and his family moved to Mentone in 1953. It was a hard period in Loving County’s history — at the time, residents had to haul in their own water from Pecos. “What I missed most when I was a kid growing up here, what I really envied, was kids that had sidewalks, streets to ride bicycles on,” Skeet says. “I wanted a bicycle so bad, but I didn’t have a street or sidewalk to ride on, just a dirt road or out in the country.” By the time Skeet was a teenager there were only two children left in the county and the primary school house where he went to school was shuttered. The “man camps,” where the oil workers lived, closed, too.

Skeet graduated from Wink High School in 1969 and attended Sul Ross University in Alpine, Texas, laid gas lines in Austin for a time, and graduated from South Plains College in Levelland, Texas, with a degree in law enforcement. He was married in 1980 to Barbara Gail Lee, and the couple lived in Wink, 30 miles east of Mentone, where Skeet worked as a pumper and a rancher. Then he followed his father Punk’s path into Loving County politics, becoming a county commissioner in 1992 and judge in 2006. “You know what the requirements are to be a county judge?” he asks. “Eighteen years old, live in the county, and be of sound mind and no felonies.” No law degree required. He laughs at the thought of this.

Despite its small size, politics have always played an outsize role in Loving County. For 70 years, three families — the Joneses, the Hoppers, and the Creagers — battled for influence, mainly to score the coveted county jobs locals depended on for income, regularly accusing one another of corruption and election rigging. By 2021, the Jones family dominated local politics. It’s been said that a third of all registered voters were related to the Joneses through blood or marriage, and many worked in county jobs that paid six figures.

As judge, a position that also administers county finances, Skeet had overseen a remarkable period of development. In 2008, the county budget was approximately $2 million. By 2020, it was $23 million. Today, it’s $56 million — roughly $1 million per capita. The county government wields outsize power, determining where that $56 million is spent, who gets lucrative county contracts, and who sits in appointed government positions.

But the boom has brought its hazards, as well, and not just local political infighting. Mexican cartel activity in the area has soared, notably oil and scrap-metal theft. Loving County’s tiny law enforcement presence is unable to counter. At least one death, the killing of an immigrant trucker, has been linked to the cartels.

After about an hour, I ask Skeet about the roots of the present-day political conflict bedeviling Loving County. Theoretically, no one would know better than him, since he’s squarely in the middle of it. He looks at me for what feels like minutes, resting his chin on tented hands — so long I’m unsure if he intends to even acknowledge the question.

Finally, he speaks. “It’s money and greed,” he says.

He explains that once the oil money started flowing, he decided to raise the salaries of most of the county positions to about the same level as his own — $126,000 — out of a sense of fairness. Now, everybody in the county competes for these positions. “That’s the biggest mistake I ever made,” he says with a laugh.

Skeet Jones was the county judge in Loving.

Photograph by Michael Magers

Throughout this impromptu meeting, Skeet speaks with a remarkable ease. This is striking, because at the time, he faced up to 20 years in prison from charges resulting from the cattle-rustling case. (Skeet denies any wrongdoing and the charges were dropped.) But that’s only the beginning of Loving County’s dramas.

IN THE MONTHS AFTER MARTY Baker first visited Mentone in 2021, according to an affidavit he later wrote, he received a series of reports alleging that Skeet and his men captured and sold stray cattle. Baker’s investigation took a turn when he developed a secret informant from the Jones family’s inner circle, who leaked text messages that suggested Skeet was illegally selling captured strays — or “wild cows,” as Skeet described them in texts — at auctions in Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. (Skeet denies the allegations in the affidavit.)

Baker obtained one image of a check for $2,720 for a cow and two steers that sold in Elk City, Oklahoma, just three days after he first met Skeet. A video taken on June 3, 2021, showed three bulls and a heifer in nearby Reeves County. On Sept. 10, the same animals were transported by Skeet himself to a sale barn in Roswell, New Mexico, according to the affidavit. They were sold a few days later for $4,433. A Texas park warden called Baker and told him he’d received claims that Skeet was using a helicopter to gather bulls and had pens set up along the Pecos River to catch strays, according to Baker’s affidavit.

When Baker questioned Skeet about these incidents and more, Skeet didn’t deny capturing and selling strays, although in some cases he said he couldn’t remember the details. But he insisted he was following Texas estray laws, and that he had an arrangement with the Sheriff’s Office to take strays directly to auction. When Baker interviewed the sheriff, an Air Force veteran named Chris Busse, who is tall with a broad forehead and a remarkable resemblance to Vince Vaughn, Busse said no such arrangement existed and he was aware of no effort by Skeet to try to find the owners.

Baker was building a cattle-rustling case against Skeet, but he needed more evidence. So, on Oct. 18, 2021, he let loose a black bull, a reddish-brown cow, and a reddish-brown calf, all of which he’d obtained for the investigation, onto a property near Mentone. The cattle were tagged with a device that would allow them to be easily identified later.

Then he waited. Baker had, in effect, set a trap for Skeet.

On Dec. 13, 2021, according to Baker’s affidavit, Skeet, dressed in a business suit, sat atop a tank battery gazing at the landscape through a pair of binoculars. Next to him was a man on horseback. Skeet was looking at Baker’s black bull, although he didn’t know it at the time. A month earlier, Skeet and his men allegedly managed to round up the two other strays and had already sold them at auction in Big Spring, Texas. But the bull was elusive, and Skeet was still trying to snag it.

It took another three weeks before Skeet captured the bull a mile from Mentone. Three days later, a trailer registered to Skeet’s ranch ferried it to Big Spring, where Baker was waiting.

“This is not quite the Hatfields and McCoys. It’s like the Hatfields and Hatfields, right? It’s brother against brother, uncle against nephew.”

County attorney Steve Simonsen

Baker confronted the driver, who said Skeet had sent him to the sale with the bull, which, the driver said, “was feral and came from the river.” He explained that the money from the sale went straight to Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch, a residence for at-risk youth northwest of Amarillo. (The Farley ranch has not been accused of any wrongdoing.) Baker asked if he knew who the bull’s owner was or if they had connected with the Sheriff’s Office. “That’s above my pay grade,” the driver said. Baker inspected the bull to make sure it was the same one he’d released — it was — and placed a hold on the bull so it wouldn’t be sold.

Now, Baker believed he had a solid case against Skeet. In all, Baker had documented 80 head of cattle that between January 2020 and January 2022 were allegedly transported from the Jones Ranch to sale yards, some of which had been identified as strays. He suspected the actual number to be higher. Skeet had had a run-in with disciplinary authorities in the past: In 2016, he received public warning from the State Commission on Judicial Conduct for changing speeding tickets to parking violations with higher fees. According to a document from the commission, Skeet claimed he did it so drivers wouldn’t lose their licenses and livelihoods. Regardless, the commission issued him with a public warning and an order of additional education. But he had never been in trouble like this. On May 18, 2022, Baker filed an affidavit requesting an arrest warrant for Skeet and three of his ranch hands, including Leroy Medlin, the county custodian at the time.

Two days later, a caravan of law enforcement vehicles drove down Highway 302 toward Mentone to arrest the judge on three felony counts of livestock theft and one count of engaging in organized criminal activity, since Baker believed the scheme was a coordinated crime ring involving Skeet and his hands. Baker was accompanied by a Texas Ranger, Sheriff Busse, and a few deputies who met them there. There were dozens of people at the ranch that day, including children and wives of the ranch hands.

Not long after vehicles pulled up, pandemonium erupted. Angela Medlin, Leroy’s wife, heard of her husband’s arrest at work at the courthouse and rushed to the scene. She tells me she was “very upset,” and when she arrived, she asked deputies, “What for? What for? Why are y’all arresting him?” The deputies pointed her to Baker, and she confronted him. Baker had no idea who she was. “You need to back up,” he said. The confrontation continued, and Baker threatened to take her to jail if she continued. (Angela was not accused of any wrongdoing. Leroy denies any wrongdoing, and Angela believes his arrest was politically motivated to prevent her husband from running for sheriff, which he was planning to do.) Tensions continued to mount when Skeet and his sons arrived, and for a moment, Baker was worried things could get violent. (“It almost got Western out there,” Baker tells me.)

Eventually, the situation calmed, and Baker placed Skeet in handcuffs and arrested him, along with Medlin and two other ranch hands. Skeet was furious. “This isn’t right,” he said repeatedly. Baker escorted Skeet to Winkler County jail where he was booked and released on $20,000 bail. (Later, a Howard County grand jury brought charges against Skeet and state regulators suspended him without pay, but he was reinstated while the case was adjudicated.) What Baker saw as a clear-cut and brazen violation of the Texas Criminal Code — a local judge seemingly living above the law, unchallenged — Skeet and his allies saw as an outrageous travesty of justice. In their minds, Skeet and his ranch hands had done nothing wrong — they were simply doing what had always been done. Why else would Skeet freely volunteer to Baker that he sometimes captured and sold strays? And besides, the sale money went to a good cause, the boys’ ranches. Skeet also argued he had a previous arrangement with the sheriff — and several sheriffs before him — about how to deal with strays.

Baker tells me that he obtained letters going back to the mid-2000s that indicated only a portion of the sale money went to the boys’ ranches, and it wasn’t until he arrived in Loving County that all proceeds began going to them. But Baker argues it wouldn’t matter if all the money went to a good cause — the law is the law. “That all sounds commendable in a way, kind of, like, a Robinhood-type deal. But the thing about it is, by law, if you’ve got an estray, the first person you’re supposed to call is the sheriff of that county. The sheriff is responsible for what happens after that.”

Steve Simonsen, the county attorney who is married to Skeet’s cousin, Jill Simonsen, the county tax collector, says the judge had an arrangement with the sheriff to take stray cattle, which are a burden to already bone-dry ranches and a disease risk for other cattle, directly to auction, and that all of the money did indeed go to the boys’ ranches. “What has been the tradition, not only here but other counties around here, is that the landowner captures the cows and then he calls around and says, ‘Hey, neighbor, you miss any cattle? I got some here that aren’t branded. Are they yours?’” Simonson explains. “Maybe they say yes, maybe they say no. So they call the sheriff, tell them what they’re going to do, and the sheriff says, ‘Look, I don’t want to fool with that. You just take care of it.’ … So they send them to the sale barn, and then whatever money they get, they donate to the orphanage.”

Instead of justice served, Skeet and his allies saw in the cattle arrests something sinister: a conspiracy on the part of Skeet’s political enemies in the county to remove them from power and replace them in coveted county jobs with the conspirators’ own friends and political allies. And at the center of the conspiracy, they believed, was Skeets’ own nephew, Constable Brandon Jones, who works just down the hall from Skeet in Mentone’s tiny courthouse.

Loving County attorney Steve Simonsen poses in his Mentone, Texas, office in June 2022.

Ivan Pierre Aguirre/”The New York Times/Redux

BRANDON IS IN HIS MID-FORTIES, tall and broad-chested with reddish hair and beard, a sun-worn face similar to the actor Josh Lucas, with blue eyes and pale lashes. He’s a Christian, and he doesn’t watch the Paramount+ drama Landman, which is based in West Texas, because it has too many curse words.

He was raised on a ranch in Winkler County, but his family long owned property in Loving. After high school, he moved to Oklahoma, where he worked on a ranch and studied agriculture business at Northeast Oklahoma A&M College. There, he met a woman from Kansas who would become his wife, Holly Diane Jones, and the couple soon had children and moved to North Texas. When Brandon’s mother became sick with cancer, the couple moved to Loving County to help care for her. In 2016, Brandon ran for constable as a Republican and won. (Skeet is a Democrat, but at the local level, party affiliation has little to do with the state and national parties.)

Not long after Brandon returned, his father, Richard, and Skeet had had a falling out. Richard no longer participated in county politics, and after his wife died, he largely withdrew from life in the county. When he moved back, Brandon and his uncle mostly got along, but it wasn’t long before they were at odds for matters small and large. The animosity between the two boiled over when suspicions grew among the Joneses that Brandon was Marty Baker’s secret informant, after a Skeet associate spotted Brandon and Baker having lunch together in Mentone.

I meet Brandon at an empty cafe in downtown Pecos, where a mix of R&B and Mexican pop plays on the speakers. We’d exchanged emails over a few months, but he wouldn’t speak on the record during the meeting about some of the specifics regarding the conflicts that revolved around him. In a May 2022 article, he told a Houston NBC reporter that Skeet has “had free reign for the entire time since he’s been the judge. That’s given him a sense of power and impunity that he can do whatever he wants whenever he wants — even the feeling of self-righteousness — that he can do no wrong.” He took a lot of heat for that quote, he told me before I came, and didn’t want to get himself in more trouble. Instead, he wanted me to ask around and decide for myself what was going on in the county.

Brandon looks like the high school football player he was; he lifts weights at a gym in a man camp near Mentone. He is dressed in the style of West Texas — Wrangler jeans, a cowboy hat, a large silver belt buckle, and scaled boots made from the leather of the pirarucu fish.

“Some people are trying to act like this is a new deal. I don’t see it,” he says when I ask about the conflict’s origins. “There’s been election contests for a while. Control over land. It’s all the same thing. Back in the Sixties, same deal.”

Brandon is visibly shaken by everything that has transpired in the county, not only the political dramas. There was also the January 2022 death of a sheriff’s deputy, Lorin Readmond, who was killed in a crash with a semi truck while responding to a call. Brandon was one of the first officers to arrive at the scene and helped extract her body from the vehicle.

“I want peace,” Brandon tells me after I ask him what outcome he’s hoping for. “I keep getting told, ‘It’s like you live in an episode of Yellowstone.’ And I would like to not. That would be the best outcome.”

ON MAY 25, 2022, FIVE DAYS AFTER Skeet’s arrest on cattle-rustling charges, came the next plot twist in Loving County’s drama and the schism between Skeet and Brandon Jones.

That day, a handful of Loving County residents reported for jury duty at a small plaster-walled room in the courthouse annex. The case was a class C misdemeanor and Brandon had written the citation, so he was there as a witness, and also as court security, which was his duty as an officer. It’s virtually impossible to seat a jury in Loving County, where so many people are related by blood or marriage. At the time, no crime had been prosecuted by jury trial in the county in four decades. Cases were punted to Reeves County, where they encountered another problem: the long-serving district attorney, Randy Reynolds, who was notorious in the state for his reluctance to prosecute crimes. (In 2008, Texas Monthly published an article about Reynolds called “The Reluctant Prosecutor,” which asked, “Is Randy Reynolds the worst district attorney in Texas?” Reynolds told the magazine that he preferred deferred adjudication, a type of community supervision, to prosecution because it does not result in a conviction on a defendant’s record. Reynolds didn’t respond to an interview request for this article.)

“I keep getting told, ‘It’s like you live in an episode of Yellowstone.’ And I would like to not. That would be the best outcome.”

Brandon Jones

Among those called for the jury-duty hearing were a county commissioner named Ysidro Renteria, whose family is close with the Jones clan; Skeet’s son Matthew; and Skeet’s nephew William Carr. The proceedings were overseen by Justice of the Peace Amber King.

Residency had long been a contentious topic in Loving County. For decades, rival groups accused one another of inflating voter rolls by having relatives who lived outside the county travel there to vote on Election Day. In 2022, for example, while the U.S. Census recorded the population at 54 people, the county’s voter roll was closer to 100. This is because of a kink in Texas voting laws that had historically allowed people to register to vote in a place even if they didn’t live there full-time, as long as they spent some time there during the year and intended to eventually return. In other words, Texans could vote where their heart was, even if it wasn’t where their home was.

But in 2021, Senate Bill 1111 changed sections of the Texas Election Code, including an amendment that stated a “person may not designate a previous residency as a home and fixed place of habitation unless the person inhabits the place at the time of designation and intends to remain.” But this caused even more confusion. What did “previous residence” mean? What if a person owned property in a place but didn’t live there full-time? Would that be considered a previous residence, or a legitimate one?

At the jury-duty hearing, King addressed those assembled. “Anyone not qualified to serve as a juror should leave,” she said. She warned that anyone not qualified who did not recuse themselves would be held in contempt of court and charged with aggravated perjury. All the prospective jurors said they met the residency requirements. “There are several jurors who are not residents of the county,” King said.

The case of the Renteria family was particularly galling for those trying to uphold Loving County’s residency requirements. Several people alleged Ysidro and his family lived in a 2,500-square-foot home in Reeves County, about half an hour drive from Mentone. But he listed as his address for voting purposes a ranch along the Pecos River with a flooded-out adobe home, a trailer, and a mobile home on stilts, all behind a padlocked gate. Other Renteria family members registered to vote at the same address.

But several people alleged that nobody actually lived there. “I can attest that I’ve been here since 2008, and there has never, ever, ever, been any of the Renterias — not even Ysidro — occupying it,” Sheriff Busse, who was in charge of voter rolls, told a reporter in 2022. (Busse declined to discuss the various cases, citing pending litigation.)

While Renteria’s ability to vote in the county was up in the air, the Texas Election Code for office holders was clearer: It required candidates for public office to continuously reside in the county they planned to represent for at least six months before they filed to run for office. Although he allegedly lived in Reeves County, Renteria had served as a commissioner in Loving County for years, earning about $55,000 a year for the part-time job. (A commissioner sits on the commissioner’s court, the county’s governing body.) The Renterias didn’t respond to interview requests. Through their lawyer, Trent Graham, they deny violating the Texas election law. “Any suggestion that he or his family improperly registered to vote or violated the Texas Election Code is unfounded,” Graham said, adding, “Mr. Renteria and his family have deep roots in Loving County. They have always maintained their ties to Loving County, even when doing so was to their detriment. His decades of service to Mentone and the broader county reflect not only his personal commitment but also his family’s longstanding dedication to the community.”

Constable Brandon Jones enters his office at the Loving County Courthouse in Mentone, Texas.

Ivan Pierre Aguirre/”The New York Times”/Redux

The Renteria family benefited from Loving County tax dollars in other ways: Multiple sources and an NBC News report claimed a trucking company belonging to Renteria’s half-brother and nephew received large contracts from the county to do maintenance work.

At the Mentone courthouse the day of the jury-duty hearing, when Renteria and the two other men refused to leave, King ordered them arrested. Sheriff Busse and Brandon Jones, acting as court security, made the arrests. They escorted Renteria, Matthew Jones, and Carr out of the courtroom into an adjoining hallway, and then into police vehicles, according to a lawsuit later filed by Renteria, Jones, and Carr against King, Brandon, and Busse. Deputies then drove the three men to the Winkler County jail “at high rates of speed, with lights and sirens blazing,” according to the suit, where they were fingerprinted, photographed, and jailed for about five hours before being released. (In court filings, King, Brandon, and Busse contended that they were merely enforcing Texas voter-eligibility laws, and argued that the case should be dismissed based on absolute or qualified immunity.)

In a matter of just a few days, the county judge, his son, his nephew, and one of his closest allies had been arrested in two separate incidents — the cattle-rustling case and the jury-duty hearing. Although the incidents were, on paper, entirely separate, Skeet and his allies believed they were linked and evidence of a conspiracy, orchestrated by Brandon and his allies, to remove them from power in the county.

In response to the contempt of court charges, Renteria, Matthew Jones, and Carr filed a federal civil rights lawsuit in the Western District of Texas against King, Busse, and Brandon. The suit, filed on Aug. 22, 2022, alleged that the defendants violated the plaintiffs’ constitutional rights in “a premeditated and vindictive scheme to punish those who were unwilling to bend to their political, personal, and financial demands.” The arrests, the suit alleged, were a partisan “ruse” to capitalize on the new Senate legislation and were used “as a pretense to summon, arrest, jail, and intimidate their political and personal rivals.” (King, Busse, and Brandon deny any conspiracy. Susan Hays, King’s lawyer, says “there’s just absolutely no valid evidence that there was ever any conspiracy,” and adds that at the time King barely knew Brandon.)

IN NOVEMBER 2022, WITH THE various lawsuits pending, Loving County voters went to the polls. Holly Jones, Brandon’s wife, lost in the county clerk race to Mozelle Carr, Skeet’s sister, by 12 votes. James Alan Sparks, the manager of a ranch near Mentone, lost by six votes in his attempt to unseat Renteria as county commissioner. And King tied Angela Medlin, the woman who had confronted Marty Baker during the cattle-rustling arrests, in the race for justice of the peace.

Sparks, Holly Jones, and King contested the results. They believed the voter rolls had been inflated by Jones family members and allies who lived out of the county but voted there nonetheless, in violation of the new Senate bill. The three hired an Austin-based election lawyer named Susan Hays (who also represents King in the arrests case) to purge voter rolls of out-of-county voters.

Hays, a Democrat who ran for Texas commissioner of agriculture in 2022, had a history battling the Joneses. She first came to Loving County in 2007, when Skeet’s brother Tom contested an election for county commissioner that he lost by one vote to a fourth-generation rancher named Zane Kiehne. Hays represented Kiehne in the case. Kiehne was frustrated with the Joneses because the county government wouldn’t grade the dirt road up to his ranch, a rambling territory along the New Mexico border. Kiehne believed the Joneses were boosting voter rolls. (Kiehne lost.) “There’s so much shit going on out there and layers of mess and bad behavior,” Hays tells me. “There’s just a constant politics to living there. And there’s people who are on the ins and people who are on the outs.”

After the 2022 election, Hays filed a suit challenging the voting eligibility of 12 members of the Jones family, including Matthew; eight members of the Renteria family, including Ysidro; and seven others. In response, the Joneses filed a lawsuit of their own challenging the plaintiff’s voters. The election-contest trial lasted two weeks, involving a dozen attorneys. Hays amassed land records and deeds, photos of interiors and exteriors of houses, and called to the stand an electricity expert to describe what low kilowatt usage might suggest about whether someone lives in a house or not. In the end, the judge removed 10 people from voting rolls, including five Renterias and one Jones. Sixteen others, including Ysidro, were deemed eligible to vote. (A judge has since set a revote on the 2022 election between Jones and Carr and King and Medlin for November 2025. For Medlin, it will be the third time running for the position in the same election cycle.)

I meet with James Alan Sparks, one of the plaintiffs in the 2022 election contest, a spirited ranch manager in his sixties with a gray handlebar mustache and an impressive Texas drawl, one morning on the back porch of the Wheat Ranch, where he lives and works, about a mile outside of Mentone. Sparks believes the reason so many out-of-county voters vote in Loving County isn’t because it’s home to them, but so the Joneses can maintain their grip on power. “It’s a mafia, man. I mean, it’s the way it works,” he says. “We need somebody to come in and run these elections. They’re so corrupt.… What happens with the county budget, if it’s $50 million, only 50 people in the county? Where does it all go?” (The Joneses have denied any wrongdoing in all of the cases filed against them.)

James Alan Sparks was a plaintiff in the 2022 election contest.

Photograph by Michael Magers

IN NOVEMBER 2022, AFTER THE ELECTION, Hays traveled to Loving County to meet with her clients and interview other residents about the alleged voting irregularities. Her clients told her about a deputy clerk named Ariel Dawn Fitzwater, who, they said, had witnessed election meddling first hand at the courthouse.

Hays arranged a covert meeting with Fitzwater in the courthouse annex. “And in walks this young woman, twenties, real cute, but deep, dark circles under her eyes. I mean, she looked like death warmed over. And I started interviewing her about what she’d seen in the courthouse,” Hays says. Fitzwater told Hays a harrowing story of alleged corruption, retaliation, even threats of violence happening at the Mentone courthouse. “I stopped the interview after about 10 minutes, and I said, ‘You need your own counsel,’” Hays recalls.

Three months later, on Feb. 2, 2023, Fitzwater filed a Texas Whistleblower Complaint against county clerk Mozelle Carr. Of all the legal dramas in Loving County, no suit contained allegations more damning for the Joneses than Fitzwater’s, whose allegations painted a portrait of naked election meddling and harassment.

Fitzwater’s suit alleged that Carr plotted to “move votes” into the county by helping nonresidents vote there and modifying voters’ statements of residency cards to make it seem like they actually lived there. When Fitzwater reported these alleged violations and others to Busse and Brandon Jones, Carr retaliated, the suit alleged, by withholding her overtime pay and her mail, and changing the password to her email so she couldn’t do her job.

Fitzwater’s suit also described the behind-the-scenes politics of Mentone’s courthouse. That included the Joneses allegedly plotting to defeat their political rivals “in alarming and violent tones, including Jacob Jones [Skeet’s son] [allegedly] frequently expressing to Ms. Medlin his desire to kill Constable Brandon Jones.” According to the lawsuit:

Ms. Carr, Ms. Medlin, Judge Jones and their relatives would often talk openly in their office about their beliefs that the Kings and Brandon Jones were evil and discuss how God would rain fire on them and they would pay, and would work on county time to research lawsuits and legal allegations that could be brought against the Kings and Brandon Jones.

The suit alleged that Carr threatened Fitzwater to not say anything about what happened in the office to anyone. “From her words and tone, Ms. Fitzwater knew that if she ever spoke up about these activities or otherwise crossed Ms. Carr and her family, her job, her husband’s job with the county, and even their family’s safety could be in jeopardy,” the suit said.

After Carr found out Fitzwater voted against the Joneses in the election and accused her of “stabbing [me] in the back,” Fitzwater reported receiving an anonymous letter with return address matching the clerk’s office: “The letter spoke in apocalyptic terms about the political conflicts in the county as struggles between good and evil and suggested that anyone who did not vote for Ms. Medlin in the tie-breaker election (for justice of the peace) was misguided by demons, would be dealt with by God, and should move out of Loving County.” (The lawsuit doesn’t say how Carr found out how Fitzwater voted, only noting that in a county with so few voters it would be easy to figure out in which direction she voted. Calls to Carr and Jacob Jones for this story went unanswered. Carr and Jacob deny the allegations in the complaint.)

Fitzwater reported the letter to Busse and Brandon Jones and filed a complaint. But with her pay essentially withheld, and denied the tools to do her job, on Dec. 12, 2023, a little more than a month after the election, Fitzwater resigned. (Skeet confirmed that the lawsuit was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount of money without any admission of wrongdoing, and according to people around town, Fitzwater and her family moved out of Loving County. Angela Medlin, who is mentioned in the complaint, says the claims are untrue.)

The alleged threats of violence in Fitzwater’s suit never came to fruition, but violence is not abstract in Loving County. One murky incident that occurred one night in early 2022 nearly led to bloodshed: Brandon was in his truck with his son hunting predators — coyotes, bobcats — when a second truck accelerated and rammed them from behind. Brandon stepped out of the truck cab with his gun drawn. The driver of the second truck was Skeet. A tense confrontation ensued.

Brandon filed a police report. Skeet confirmed the accident but said it was a case of mistaken identity. “It was out on private property. I thought I saw a hunter on our property at night. We were hunting predators with a spotlight. He took off running and I was chasing him and caught up to him on a dirt road and he slammed on his brakes and brake-checked me, and I just barely bumped him in the back end.… There was no intention to harm anybody. In fact, there was no damage done to either vehicle.” (The Loving County Sheriff’s Department denied a Freedom of Information Act request I made for documents related to the incident, citing law enforcement exemption.)

“What happens with the county budget, if it’s $50 million, only 50 people in the county? Where does it all go?”

James Alan Sparks

IN FEBRUARY 2025, I MAKE A second visit to Loving County. Since my last trip, the Howard County district attorney had dismissed the cattle-rustling charges against Skeet, Leroy Medlin, and the other cowboys. The charges were later also dropped in Reeves and Loving counties. (“The charges should never have been brought in the first place,” Skeet’s lawyer, Jason Davis, tells me.) Another election had passed, and a new spate of election challenges had been filed by both sides. Skeet and Brandon won their contests. Leroy Medlin lost in the Republican primary to David Landersman, a former sheriff’s deputy.

Landersman went on to unseat Busse as sheriff. Busse is now working as a sheriff’s deputy in Winkler County and is unsparing when he describes his feelings about life and politics in Loving County, and the Jones family. “I was glad I didn’t win the election,” he tells me over the phone. “It’s just a cesspool of wrongdoing with Machiavellian politics, using deliberate evil to advance whatever goals they have, unimpeded, and nobody gives two shits about it.”

The previous November, Brandon, who recently became a grandfather, won his reelection campaign by a single vote against his own second cousin, Tyler Simonsen (Simonsen contested the results; the contest is still ongoing). In March 2025, Ysidro Renteria, who had recently added some additions to his property in Mentone, filed an application for a temporary restraining order and injunction against Brandon, accusing him of harassment and intimidation. In the filing, Renteria claimed that Brandon “acted inappropriately during Commissioner’s Court, staring at Plaintiff and raising his eyebrows in an intimidating manner” and that he “continued harassing Plaintiff by blowing kisses at him, mocking and attempting to intimidate Plaintiff in a public setting.” (Brandon denies threatening anybody, and the request for an injunction was later dropped. Meanwhile, in August 2025, a U.S. appeals court overruled a district court ruling in the federal civil rights lawsuit filed by Renteria, Matthew Jones, and William Carr, by finding that Amber King, Brandon Jones, and Chris Busse were shielded by judicial immunity in the jury-arrests case. The court dismissed a cross-appeal filed by the plaintiffs due to lack of jurisdiction.)

It was also Renteria who, in October 2024, filed a motion to slash the salaries of the constable and sheriff. The county then introduced a budget proposal that cut the sheriff’s salary in half and the constable’s salary by 75 percent, to $31,000. When I ask Skeet over the phone about the cuts to the law enforcement salaries, he says, “It’s nonperformance and bad behavior, unscrupulous behavior.” He explains the sheriff had been operating without oversight, signing contracts and changing locks without permission, and that both the sheriff and constable weren’t patrolling or writing tickets. (Both Busse and Brandon Jones deny these allegations and have said the budget cuts were an act of political retribution.)

The cuts to the law enforcement budget came during a record budget season. Indeed, the answer to the question Alan Sparks raised about what happens to all of the money flowing through the county government is one that even local authorities are unable, or unwilling, to answer. In 2025, the total projected tax revenue in Loving County is $55.4 million, up from a projected $40.2 million in 2024. Meanwhile, in 2024, the county projected a budget deficit of $4.5 million, but ended with a $56.4 million cumulative surplus.

Some notable recent budget items include: $24.5 million, nearly half the budget, allocated in 2025 to the water fund; $14 million over the past three years for “courthouse renovations,” none of it spent; $15.5 million this year for a new fire hall after a $12 million transfer last year, with only $1 million actually spent; and a $20 million road and bridge surplus from last year.

The county has conducted no audits on its budget since 2020, as required by the state. (County attorney Steve Simonsen says the county is currently conducting audits for 2022 and 2023. The county denied FOIA requests filed looking into the water district’s finances.)

By comparison, Kings County, Texas, which is home to some 270 people, more than four times the population of Loving County, has a total annual budget of just $2.74 million.

THERE WERE A FEW DEVELOPMENTS since my previous visit that could mean lasting change in Loving County. First, there’s a new district attorney in Reeves County. A young Republican lawyer named Sarah Stogner had unseated the longtime incumbent Randy Reynolds. She’d been recruited to run by a group who wanted to bring legal accountability to West Texas. One case she inherited was a series of child rapes at a local children’s detention facility in the early 2000s. Her campaign platform was, essentially, to “not let child rapists walk away,” Stogner says when we meet at her office one morning in a single-story, unmarked government building in downtown Monahans, an hour’s drive from Mentone.

Photograph by Michael Magers

Since, she claims, she inherited a mess of cases when she took office, bringing oversight and accountability to Loving County isn’t one of her top priorities. But that doesn’t mean it’s not on her mind. She says she’s been speaking with state legislators about how to get around the problem of seating a jury, while also looking into various allegations of wrongdoing in the county. “We are investigating crimes in Loving County. That’s all I can tell you,” she says.

Stogner does tell me about her first meeting with Skeet, when she was visiting Loving County and meeting with members of the Sheriff’s Department during the election. “I guess it was during early voting, and Brandon told me, ‘Hey, you’re being watched. Skeet’s truck is parked across the street,’ just like surveilling us. And so when I went to leave, I just went up and introduced myself. And he’s like, ‘Oh, I’ve already voted.’ And I was like, ‘I wasn’t asking for your vote. I was just introducing myself.’”

I ask how Skeet responded. “That was it. I just wanted him to know that I knew he was watching me,” she says.

Another strange development in Loving County involves a mysterious figure and self-proclaimed 2028 presidential candidate named Dr. Malcolm Tanner, who has launched a plan to build 100 homes in the county and give them away to 100 families for free. Some of his followers have already moved to a plot of land outside Mentone and registered to vote. Tanner then plans to take over the county government — ousting the Joneses from power — and changing the name of Loving County to Tanner County, according to a recent story in the Houston Chronicle.

A third notable development was a new Senate bill, introduced by State Sen. Kevin Sparks, that would allow Loving County to recruit residents of neighboring counties to sit on its juries, as long as they met all other necessary requirements.

In May, Brandon traveled to Austin to testify in support of the bill at the Texas State Capitol. Wearing a charcoal blazer, jeans, and cowboy boots, his hat on the wooden table in front of him, he described the many challenges faced by the county he serves. “If you look around this room, I counted 62 people — that is eight fewer than the population of my county. That’s a debatable matter, though.”

Brandon, his nerves showing, spoke about the oil boom, cartel activity, copper and crude-oil theft, and the struggles the six law enforcement officers in the county have dealing with it all. “Even with our best efforts, if we were to make an arrest, we would go two to three years without getting a grand jury,” he said in the Senate chamber. “Our criminal justice system is not necessarily broken. It’s nonexistent.”

He added: “We have a cyclical issue with public corruption, with no prosecution. This bill, I think, addresses those issues. I don’t think it fixes all of it, but it does a very, very good job of addressing our issues.”

TO THIS DAY, THE CASE OF THE DEAD COWS remains unsolved. But people have their theories. “I figured it out. I know who did it,” Skeet tells me. “Brandon did it. My nephew.” I ask him how he knows. “Intution, and knowing my sweet little nephew.” In fairness, Skeet adds that, back in March 2021, the sheriff’s department had been trying to gather the stray cattle for days, and he thinks Brandon shot them to get them off the road. “In fact, if I was law enforcement, that’s what I would have done.” Skeet says he no longer speaks with Brandon. “I see him and I go the other way,” he says. “I’m trying to keep the peace. We get into a conflict anytime we talk.” (Brandon says he was in El Paso at the time of the cow shootings and denies any involvement.)

In July, Skeet, the P&M Jones Family Ranch, and the three ranch hands arrested in the cattle-rustling case filed yet another lawsuit, this one against Skeet’s brother, Richard, and daughter-in-law Holly, asking for more than $1 million in monetary relief for their alleged roles in Baker’s investigation. The suit centers around the claim that Richard, who once sat on the ranch’s board, and Holly, who worked as its accountant, knew that all of the money obtained from selling stray cattle went to the boys’ ranches, and that they withheld that knowledge from Baker as part of a conspiracy to defame Skeet and others. According to Hays, who is representing Richard and Holly, no such conspiracy existed, and whether or not Richard and Holly knew whether the money went to boys’ ranches is irrelevant, since Baker’s case was focused on violating estray laws, not any financial motivation. Hays has since filed a counterclaim by Richard, accusing the P&M Jones ranch of making “illegal political contributions to benefit insiders and Skeet Jones’ political allies.” (Jason Davis, the ranch’s lawyer, says the ranch denies the counterclaim.)

Baker, who recently left his job in Coleman to become a district attorney investigator in the 143rd Judicial District Attorney’s Office, which covers Loving County, has his own theory about who killed the cattle. “I don’t know who shot the cattle, but a week prior to that, there was one of those estrays that got hit on the other side of the bridge, just inside Reeves County. And I think whoever that was … probably saw those cattle out there on the side of the road and just was pissed off and come up there and just started shooting them, because, I mean, I guess they were a nuisance. It’s a public-safety issue, right? Crossing a major highway in the dark, and this kind of thing? So I mean, I think a citizen probably done it just out of, I don’t want to say spite, but out of frustration. ‘Dang cow!’ This kind of thing.”

Baker adds: “The narrative is that this is a conspiracy. It was a set up. Lemme tell y’all, it was never a setup. Skeet and his bunch are going to swear up and down that Brandon has caused all this. But I’m here to tell you, he’s not.… He was the only one trying to do things right. And I think, I can’t speak for Brandon, but I will say this, I think that of course Brandon’s part of that family and was probably brought up seeing this stuff, not realizing that it was illegal. After he become a constable, he starts putting all this stuff together and it’s, like, ‘Holy crap, man, y’all got to stop this.’

“I’m telling you, man, this deal out here is bigger than … It’s a bigger scale than what everybody knows.”

ON MY LAST DAY IN LOVING COUNTY, driving on the highway from Mentone to Pecos, the same highway Baker drove in March 2021, I pass the carcass of a cow on the side of the road. It was there on my first trip, and there it is still, a pile of bones, tendon, and shriveled hide. It’s a perfect, if macabre, symbol of the story I’m working on, one that started with dead cattle on the side of the road, the event that sparked the feud that still plagues the county.

As I make my way to Pecos, looking out over the landscape I’m reminded of something Brandon told me over coffee in Pecos during my first trip to the area six months earlier. “There are beautiful things about this part of the country,” he said in a voice so quiet it was difficult to hear over the pop song playing on the coffeeshop speakers. “The sunsets are unbeatable. The night sky is incredible. The smell after a rain is indescribable. You can love this country, and this area, but it …” He paused for a moment. “It’s, you know, ugly country, too.”